Research about power and power sharing

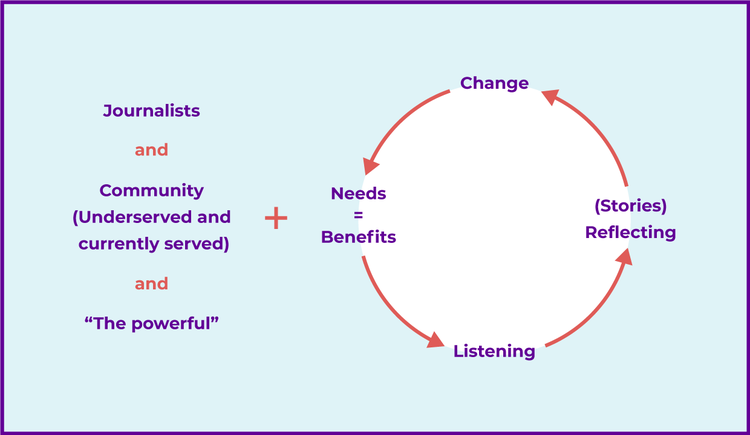

One focus of my research has been around the idea of power in journalism and communities.

For the Membership Puzzle project, I took the community organizing idea of power sharing and applied it to journalism. I wanted to take the idea that journalists inherently have power, and the best form of engagement is sharing that power with our communities.

As a capstone project for my time at CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, I took that idea further, applying the idea of power mapping to reporting. Many newsrooms map beats to a funnel or other audience map, but few examine their role in distributing power.

Membership Puzzle Project: Redistributing power in communities through involved journalism

In college, I received an enamel pin. It shows a typewriter with a skull and crossbones. “Write Hard, Die Free,” it reads. It’s an expression of the idea that journalism is a calling, that this profession is a staple of democracy, the Fourth Estate. It exists to hold truth to power. Journalists are here to give voice to the voiceless and empower citizens with news and information. I have ordered this pin to give as a gift for many years, and especially lately as it seems our power is being called into question.

The American Press Institute makes specific note of this in their Journalism Essentials:

Viewing the reader as less a consumer or audience member and more a decision-maker is a good place for the journalist to start. In one sense it’s about self-respect – an assumption the reporting will have some utilitarian value – and respect for the reader, a belief that the audience really does want to make the best possible decisions.

We’re in yet another era of journalism consolidation and innovation in journalism, depending on whether you’re a glass-half-full or glass-half-empty kind of person. Building trust with audience members and engaging them where they gather is a concept that, excitingly, is gathering more traction.

Part of the hope in engaging our audiences is to bring them into our funnels and hopefully convince them of our worthiness of their membership. For many people in marginalized communities, paid news subscriptions and memberships are out of reach. They are struggling with rising rents, healthcare costs, and underemployment. Giving a news outlet $10 or even $5 seems impossible, especially when so much news is “free” on the internet.

On the other side, as newsrooms shrink and consolidate, we’ve lost touch with our readers, viewers, and listeners (for those organizations that were in touch in the first place). It’s a rare luxury to have a reporter to cover every school district and more likely that a single reporter is expected to cover all schools in a metropolitan city.

Combine these two issues and you have a bit of explanation for the rise of projects revolving around training citizens. Traditionally surrounding the idea of community contributors, the more modern version of these involves training and mentoring.

With dwindling time and resources in newsrooms, does it make sense to invest in citizen-powered journalism and training? These programs might accomplish the mission of many newsrooms and improve democracy as a whole, but do they actually change communities? There are plenty of places to seek answers, because there is no shortage of programs that seek to train and “empower” people on behalf of journalism. At least part of the answer lies in those existing programs and their successes and failures. I want to understand the ingredients of a successful strategy to shift power within communities through training and journalism contributions, and whether people who were involved stay involved or become more active citizens.

Why this is relevant to membership? Knowing whether involvement and training qualifies as a “sufficient” investment to warrant membership (by boosting the overall knowledge and information available to a community) can help us understand how people might pay in participation.

In “Understanding Alternative Media Power: Mapping Content & Practice to Theory, Ideology, and Political Action,” author Sandra Jeppesen wrote about the theory of citizen produced media this way: “People producing citizens’ media develop a growing sense of themselves as participants in democratic decision-making, able to influence policy-makers and shape the direction of their local communities, often addressing inequities and human rights violations.”

That is my hope. The idea of non-financial contributions from the community comes with the hope that it contributes to public knowledge. In training citizens to commit acts of journalism, they might feel more empowered. These trainings may teach people to be the record for city council meetings, or asking people in countries where journalistic resources are scarce to write about what is happening. They might translate articles or submit FOIA requests. They might be more likely to vote or more likely to run for office or advocate for issues. In some cases, this is very much true and possible, but it depends on many factors, primarily the relationships between news organizations and citizens.

But I believe we need relationships between the powerful and the people who lack power to tip the scale.

CUNY: Practical Power Sharing

Journalists often say their purpose is to “hold truth to power,” but as technology has changed information consumption, journalists have sought to build trust and re-establish their role beyond shining light on misdeeds of the powerful, more to shining light on people and stories that expand one’s worldview and understanding.

Power sharing is originally a concept from community organizing, often defined as a process where group members aim to build sustainable movement by creating relationships rooted in trust and shared leadership. Essentially, when the group with more power recognizes the power imbalance and takes steps to level the playing field

In the age of America’s race reckoning and #MeToo, this type of journalism has become the subject of much fascination, and I have done some of the early research on this in 2019. But the remaining question is how to bring these principles and philosophy down to a practical level.